“If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world.” -J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit

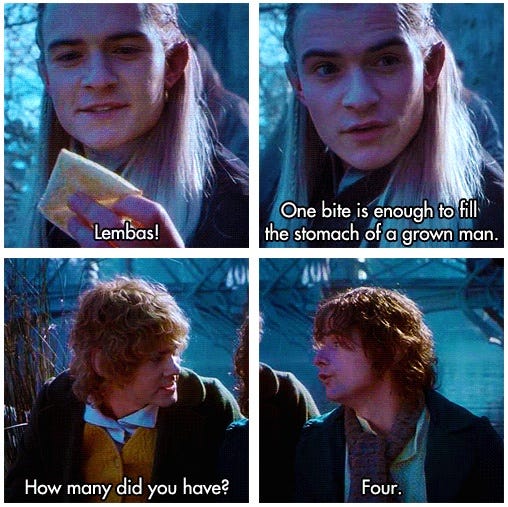

Temperance is probably not the first word that comes to mind when one thinks of J.R.R. Tolkien’s hobbits. If anything the Hobbits seem gluttonous. They eat twice as many meals as the average human; they throw lavish parties with more gifts and libations than anyone could reasonably finish in an evening; and they do it all with merry abandon, with a jocularity that our consciences (and our waistlines) sadly won’t afford us.

Why then does the Hobbits’ way of life not repulse us? On the contrary, it charms us. It draws us in. These beings with their creature comforts awaken in us a craving for the good life. Why is this? It is because the Hobbits understand something about pleasure that we often forget. Their approach to pleasures, contradictory as it may seem, is a lesson in the virtue of temperance.

Temperance, like all virtues, is a positive thing. It is a “yes” more than it is a “no.” While in our fallen world it often must take the form of “no,” denial is not its truest nature. We do not practice temperance because pleasure is bad. We practice it so we can recover a proper relationship to pleasure again. God created us good, and he gave us the world as a gift.

In the beginning our desires were not bent but properly ordered. Pleasure was the sign from God that we were doing what was truly good for us. Now, our desires are often bent. We want what is good, but in the wrong way, at the wrong time, to the wrong extent, and without God’s help. Temperance is the virtue that helps guide our desires back to the right path. It is not there to destroy our desires, but to sanctify them. Like chastity, temperance only asks that we deny ourselves in order that we may experience pleasures in the right way. It sculpts our hearts to love again what is right and enjoy it with freedom. The enjoyment is an important part of the journey.1 The goal of temperance, like all of the virtues, is not denial but life abundant.

Tolkien’s Hobbits stand as an objection to the notion that temperance is all about saying “no.” Temperance is fundamentally a “yes” to enjoying the world the way it was meant to be enjoyed. It is a resounding affirmation of God’s original plan for man’s pleasures. This “yes” is made more courageous in the face of original sin, for it requires that our yes would also function as a battle cry, a promise to fight against the wayward desires of the flesh until true freedom is attained.

The Hobbits show us how to enjoy the world as it is, without shame. When God made the world, he did not intend for man to have to fight against his own desires. Man was not created to be at war with himself, but to delight in the world with pleasure as a guide for what is good. It is hard for us to imagine what this would look like, but Tolkien’s Hobbits give us a clue. Whereas we cannot eat and party without a niggling sense of shame that we may have gone too far, the Hobbits have no such scruples. They revel in the splendors of life because they understand the fundamental truth that original sin has obscured in us: life is a gift, pleasure was originally good, and this world was given to man as a sign of God’s goodwill towards us.

Now, that is not to say that we should throw caution to the wind and skip blindly down the path of pleasure-seeking. In our current state, we have to fight for the virtue of temperance through effort and much self-denial. This is why it sometimes feels as if temperance is the virtue of always saying “no.” However, the Hobbits are a valuable example for us, even in our broken state. They remind us of what it looks like to reach the end of the journey. They remind us that the goal is not to eradicate pleasure, but to redeem it. They remind us that the road of self-denial does not lead to an empty table, but to a feast. The tomb leads not to death but to life (and as Sam Gamgee would be glad to hear, a garden). This is how our lives are meant to be enjoyed: with ordered pleasure, freely, and without shame. It is no wonder, then, that heaven is described as a banquet.

The Hobbits hold up a mirror to our lives and force us to ask the uncomfortable question: Am I able to enjoy the world as God intended? Am I able to take part in the overflowing gift of creation? If not, what needs to be reordered and repented of, so I can delight in the world God made? If we pay heed to the temperance of Hobbits, perhaps we will be closer to answering these questions.

It is essential that we should first be well steeped in the 'homeliness', the frivolity, even (in its best sense) the vulgarity of the Hobbits; these unambitious folk, peaceable yet almost anarchical, with faces 'good natured rather than beautiful' and 'mouths apt to laughter and eating', who treat smoking as an art and like books which tell them what they already know.

-C.S. Lewis, from his review of “The Lord of the Rings”

Maddie Dobrowski is an author and educator. Her book, “The Lord of the Rings and Catholicism,” can be found here.

After my students finish reading Plato’s Gorgias, in which he refutes the Sophists’ claim that pleasure and virtue are the same, I like to revisit the topic of pleasure with them through the lens of St. Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas argues that pleasure is a necessary part of reaching the final end goal of life. In other words, it is a necessary part of what virtue prepares us for. The pleasure Aquinas talks about is not a physical pleasure, but the pleasures of this earth can nevertheless point us to and prepare us for that goal, provided that they are properly ordered.

This was so beautifully written—thank you, Maddie.

Your framing of temperance as a “yes” more than a “no” reminded me how easily we forget that virtue is about joy, not deprivation. The Hobbits embody this so tenderly: their feasting isn’t gluttony—it’s gratitude made visible. Their cheerfulness, their love of gardens, their midday songs—it’s all a quiet theology of enough.

The connection to Aquinas is spot on. Ordered pleasure isn’t indulgence—it’s alignment with divine design. The Hobbits don’t fear delight; they simply don’t hoard it. And that makes all the difference.

Loved the image of the tomb leading not to death but to life—and of course, to Sam’s garden. What a subtle and powerful way to show how denial gives way to abundance.

What an interesting perspective! I had not thought of temperance or moderation as a virtue of hobbits. I need to go back and read Tolkien again!

Tolkien seems to have wanted to create something distinctively English - not Latinized, not Hellenized - yet temperance and moderation are hallmarks of Greek philosophy particularly. And to me, the hobbits seem to embody the virtues of the yeoman or husbandman - attached to the soil and its simple pleasures, but avoiding overindulgence because, like any people who are attached to land but lack great wealth, they know that abundance and want are two sides of the same coin.

A failure of temperance is typically a failing of those who have too much, which is why the teaching of the Greeks is so relevant now, when the powerful in most societies have far too much. The hobbits, though, live a much simpler life. Perhaps what Tolkien is really emphasizing is the benefit of not having too much, and the discipline engendered by having just the right amount.