“Hey! Come merry dol! derry dol! My darling!

Light goes the weather-wind and the feathered starling.

Down along under Hill, shining in the sunlight,

Waiting on the doorstep for the cold starlight…”

-J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring, Chapter 6

It still amazes me that in the wake of two horrific world wars, the industrial revolution, and the rise of technology, all of which ushered in a choking modernism, fraught with despair, J.R.R. Tolkien’s response was…

“Give ‘em Tom Bombadil. That’ll fix them.”1

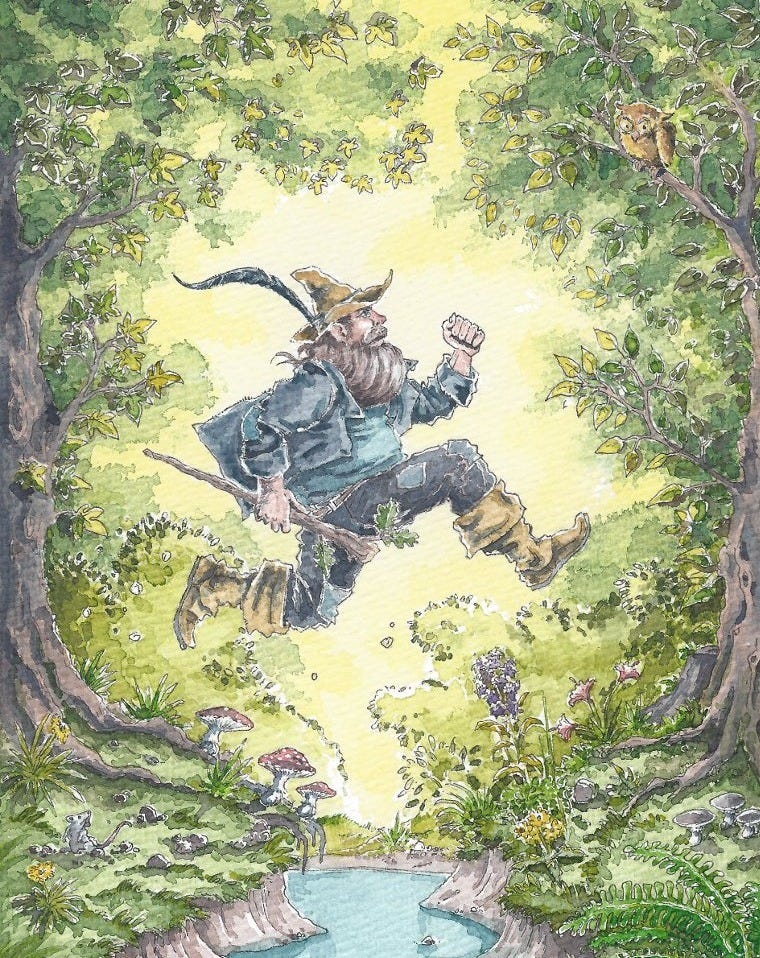

Tom Bombadil is a controversial character in Tolkien’s lore. Some love him, some hate him, and others simply don’t understand him. He isn’t controversial due to anything he does in the story. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. Tom is controversial precisely because he doesn’t do much. He befuddles. He frustrates. He evades analysis. In short, Tom is full of nonsense.

Bombadil dances in and out of meaning, refusing to be pinned down by a single interpretation. Like Father Christmas in Narnia, some throw up their hands and conclude that he is better left out of the story altogether. What on earth are we to do with this maddening, gladdening character?

Despite the dissenting voices, I would argue that Tom is actually central to Tolkien’s storytelling. If we miss the point of Tom Bombadil, we miss one of the main points of Tolkien’s entire enterprise. This becomes more clear when we look at the context in which Tolkien wrote his stories.

Master of the Withywindle

First, a brief history of Tom’s character is due. In the words of the man himself, Tom is

“Eldest, that’s what I am… Tom was here before the river and trees; Tom remembers the first acorn… He was here before the Kings and the graves and the Barrow-wights. When the Elves passed westward, Tom was here already, before the seas were bent. He knew the dark under the stars when it was fearless — before the Dark Lord came from Outside.”2

In the words of his wife Goldberry, Tom simply is.3 Finally, in the words of Tolkien, Tom is… pointless!4 Tolkien encourages his readers to stop overthinking the meaning of Tom. “As for Tom Bombadil, I really do think you are being too serious, besides missing the point… I don’t think Tom needs philosophizing about, and is not improved by it.”5

Why would Tolkien add a pointless character? Didn’t our high school English teachers tell that nothing is pointless in great works of literature?

“Mooreeffoc” and Recovery

The answer to the enigma of Tom Bombadil is found in Tolkien’s essay “On Fairy Stories.” There, Tolkien discusses a key element of fairy stories. This is the element of “newness” that helps us to look at the world with clear eyes again. Fairy stories take the primary colors of the real world and create something new with them. When we encounter these colors through the medium of fairy stories, we are “startled anew” by the miracle of the world we live in.6 This is a gift, which Tolkien calls recovery.

To achieve recovery, it is necessary that we look at the world through a new angle. Tolkien borrows from Chesterton to explain this.

“Of course, fairy-stories are not the only means of recovery… Humility is enough. And there is Mooreeffoc, or Chestertonian Fantasy. Mooreeffoc is a fantastic word… It is Coffee-room, viewed from the inside through a glass door, as it was seen by Dickens on a dark London day; and it was used by Chesterton to denote the queerness of things that have become trite, when they are seen suddenly from a new angle.”

- J.R.R. Tolkien, “On Fairy Stories” in The Monsters and the Critics, ed. Christopher Tolkien (London: HarperCollins, 1983), 146.

Tom Bombadil muddles the brain, to be sure, much like encountering a backwards word written on a glass door. But this idea of Mooreeffoc is not enough to entirely explain his character. After all, Tom is not simply confusing. He is maddening. The word “nonsense” is used three times within the first two pages of his introduction to the story. Even the hobbits are confused by him. Frodo asks twice who he is. Clearly he is not satisfied with the answer he gets. Tom Bombadil is not the regular world wrapped up in new light. He is entirely other.

Perhaps we need to attend to what Tolkien says next. After discussing Chestertonian Fantasy, Tolkien introduces another idea, that of Creative Fantasy. He contrasts this with Chestertonian Fantasy. Tolkien says that Chesterton’s idea of recovery is good. However, it is limited “for the reason that recovery of freshness of vision is its only virtue.”7 Creative Fantasy, on the other hand, does not merely help you repossess the world. It aims instead to make something new, and in doing so it sets the world free from your possession.

“The word Mooreeffoc may cause you suddenly to realise that England is an utterly alien land… to see the amazing oddity and interest of its inhabitants… but it cannot do more than that… Creative fantasy, because it is mainly trying to do something else (make something new), may open your hoard and let all the locked things fly away like cage-birds. The gems all turn into flowers or flames, and you will be warned that all you had (or knew) was dangerous and potent, not really effectively chained, free and wild; no more yours than they were you.”

- Tolkien, “On Fairy Stories,” 147

Tolkien is making a metaphysical claim here. Although he hesitates to include himself among the philosophers, he is making a philosophical claim about how reality works. Reality contains within itself the potential to be more than what we see. This potential is brought into actuality through our creations. We were not meant to be slaves to Nature, nor were we meant to be her master (in the sense of the mastery employed by Saruman). We were meant to be Nature’s lovers. “The storymaker who allows himself to be ‘free with’ Nature can be her lover not her slave.”8 This freedom allows us to enjoy the full height and breadth of nature, instead of being locked into one way of viewing things.

Take for example the city of England. Mooreeffoc may help you to see England itself again with wonder; but Creative Fantasy will set you free from thinking that England is the prototype for all cities. Creative Fantasy will allow you to conceive of cities beneath the sea, cities above the stars, and in doing so recover a broader definition of the word “city” itself.

Hey! Come, merry dol! derry dol! My darling!

We see in Tom Bombadil this very attitude. Tom is the Master of the Withywindle, but he does not own it (an important point). Goldberry is shocked when Frodo asks if Tom possesses the land (see footnote three). For Tom to be Master of the land simply means to be its lover, to delight in it for what it is and for what it can become. Tom, if he represents anything at all, represents a pure love for the natural world. He represents the spirit of the land, where sheer existence is good in itself, apart from any utility we can squeeze out of it. This is why Tolkien wrote that if Tom is an allegory at all,

“He is… an allegory, or an exemplar, a particular embodying of pure natural science: the spirit that desires knowledge of other things, their history and nature, because they are ‘other’ and wholly independent of the enquiring mind… entirely unconcerned with ‘doing’ anything with the knowledge.”

-Tolkien, Letters, Letter 153, ed. Carpenter, 192.

Nonsense: The Answer to War and Industrialization

Tolkien was writing The Fellowship during World War II, after having lived through World War I. He watched as industrialization swept through the countryside. Society was moving towards a utility-based relationship with the land. People had been reminded of the fragility of life, and as a result they were scrambling to build and repossess. Many of the places that Tolkien grew up in were being mowed over to make room for more buildings.

Tolkien’s lament over the loss of the natural world ran much deeper than his simply being a tree-hugger. He sensed that society was moving away from viewing nature as a gift. We were clinging and grasping at resources instead of living with an abundance mindset. Like the Brandybucks who hack at the Old Forest when it encroaches upon their land, people began to fear the woods instead of loving them. In a broader sense they feared the world instead of loving it.

So yes, recovery is needed. But most importantly we need to recover the attitude of Tom Bombadil, who loves the world for its own sake. This may seem like utter nonsense in a world that is driven by efficiency and production. But it is precisely what we need.

If we want to understand Tom Bombadil, we have to accept him on his own terms. Tom is full of nonsense, and that is a good thing. Tolkien wants us to rediscover the world through the eyes of Tom Bombadil. To do this, we have to see the world as “nonsensical.” This does not mean that the world is not logical. It simply means that the true value of the world surpasses our narrow ideas of means and ends. The true character of the world is wonder and delight. Tom invites us into that attitude.

If we embrace the “nonsense” of Tom Bombadil, perhaps we will become wise enough to experience the delight that comes through viewing the world as truly enchanted. If we dance through the Withywindle with Tom, we may emerge to see that all woods are a little bit enchanted.

Maddie Dobrowski is an author and educator from the Pacific Northwest. Her book “The Lord of the Rings and Catholicism: Exploring the Christian Roots of the Lord of the Rings Trilogy” can be found here.

Not an actual quote from Tolkien.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring (New York: Ballantine, 1965), 182.

“‘Fair lady!’ said Frodo again after a while. ‘Tell me, if my asking does not seem foolish, who is Tom Bombadil?’

‘He is,’ said Goldberry, staying her swift movements and smiling. Frodo looked at her questioningly. ‘He is, as you have seen him… He is the Master of wood, water, and hill.’

‘Then all this strange land belongs to him?’

‘No indeed! … That would indeed be a burden.’”

Tolkien, The Fellowship, 173-174.

“And even in a mythical Age there must be some enigmas, as there always are. Tom Bombadil is one (intentionally).” J.R.R. Tolkien, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter 144, ed. Carpenter (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981), 174.

Tolkien, Letters, Letter 153, ed. Carpenter, 192.

“We should look at green again, and be startled anew by blue and yellow and red. We should meet the centaur and the dragon, and then perhaps suddenly behold, like the ancient shepherds, sheep, and dogs, and horses — and wolves. This recovery fairy-stories help us to make. In that sense only a taste for them may make us, or keep us, childish.” Tolkien, “On Fairy Stories,” 146.

Tolkien, “On Fairy Stories,” 146-147.

Tolkien, “On Fairy Stories,” 147.

Another significant scene is where tom gives the ring back to Frodo as if it is nothing. The wise are afraid of even seeing the ring. But Tom puts it on and then returns it immediately. He is the only character free of posessiveness and domination. Even hobbits can be possessive but for Tom that is all nonsense. He is fully in tune with nature

I always loved Gandalf's argument for not giving the Ring to Bombadil, because he would care so little about it that he would likely lose it.